Archbishop Laud

Strange! That thy hand should not inspire / The beauty only, but the fire: / Not the form alone, and grace, / But act and power of a face.

Edmund Waller, To Van Dyke, 1630s

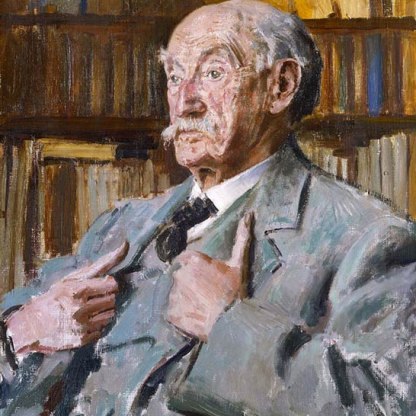

The ageing, ruddy man in this portrait may not display the kind of lavish beauty with which Sir Anthony Van Dyck endowed many of his female sitters. But his face does evoke the 'power', and perhaps something of the 'fire', to which Edmund Waller refers in his tribute to the artist.

Archbishop Laud stares directly at the viewer, commanding respect. His eyes are illuminated by intelligence but their heavy lids and raised, arched brows give him a distant, even haughty air. There is little humour or warmth in his expression. A contemporary once dismissed Laud as 'a little, low, red-faced man', but Van Dyck's archbishop is no weakling or figure of fun. His small stature is compensated for, even masked by, his being shown here in three-quarter-length, dressed in a bulky eccesiastical uniform.

This sense of quiet authority is reflected in Laud's stance. He rests his right elbow upon a pillar, a pose that Van Dyck borrowed directly from the great Italian painter Titian. Both artists used it for figures in whom they wanted to suggest integrity and power. The treatment of the archbishop's hands in Van Dyck's painting has been singled out for particular praise. Is there a suggestion of restlessness, of impatience in his parted fingers? Does the archbishop have better things to do than stand around posing for portraits?

The artist's great achievement is in conveying this sense of authority chiefly through his sitter's posture and facial expression. He does not need to use emblems here, or exaggerate the physicality of his subject. In this respect Van Dyck's image of Laud is as far from his extravagantly symbolic portrait of the countess of Southampton in the Fitzwilliam [PD.73-1978], as it is possible to be.

Yet the brilliantly painted white surplice, with its billowing sleeves, may denote more than the archbishop's office. Austere though it is compared with the satins and silks worn by the dandies of Charles I's court, it is nevertheless a garment that was loaded with significance in Laud's day. In the wake of the Reformation, Puritans in England had sought to do away with much of the paraphernalia that attended Roman Catholic rites, and the surplice was seen as a regrettable relic of idolatrous pre-Reformation worship. Laud, who throughout his life staunchly defended the material aspects of Christian worship, disagreed. He regarded the surplice as a perfectly acceptable and dignified item. In 1640 he wrote:

All that I laboured for ... was that the external worship of God ... might be kept up in uniformity ... decency and some beauty of holiness.

The red and gold curtain, hanging in the top right of the painting, might be a reference to altar cloths, the use of which the archbishop also defended against the Puritans.

More than forty copies of this painting survive, so admired was it in the seventeenth century. It was only after cleaning in 1981, however, that the supreme quality of the Fitzwilliam version was recognised. It is now thought that this is the original from which all other copies derive – that painted by Van Dyck in 1635, and given by Laud to St John's, his Oxford college.

Van Dyck was himself a Roman Catholic, but he spent nine busy years in Protestant England from 1632, when he was knighted by Charles I and appointed 'principalle Paynter in ordinary to their majesties'. It was perhaps Catholic sympathisers like Archbishop Laud who made him feel welcome in Protestant England.

William Laud was appointed archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, and throughout his tenure of the office, he energetically promoted a form of high Anglo-Catholicism within the country. He found himself consistently at odds with the Reformers and Puritans.

In his diary for 27 October 1640, Laud mentions an unsettling incident involving a painting of him:

In that study hung my picture, taken by the life. And coming in, I found it had fallen down upon the face, and lying on the floor. The string being broken, by which it was hanged against the wall. I am almost every day threatened with my ruin in Parliament. God grant this be no omen.

Less than two months later, he was arrested for treason and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Earlier in the year he had declared that the King ruled by divine right and that those who opposed him – a large faction in Parliament – faced damnation. Laud's attitude towards the Puritans was uncompromising. His attempts to impose the English prayer book upon Scotland eventually led to his impeachment by Parliament and sowed the seeds of the English Civil War which broke out in 1642.

Laud languished in the Tower of London for four years before standing trial. By this time the Royalists were losing the Civil War, and the king could do nothing to protect him. In 1645 Laud was sentenced to death and beheaded.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Anon. sale, Christie's, 30 January 1920 (267); coll. Charles Ricketts and C.H. Shannon

Legal notes

The Ricketts and Shannon Collection. Bequeathed by Charles Shannon, 1937

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1937

Dating

Formerly 'Studio of van Dyck'.

Maker(s)

- Dyck, Anthony van Painter

Note

Formerly 'Studio of van Dyck'.

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordOther highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…