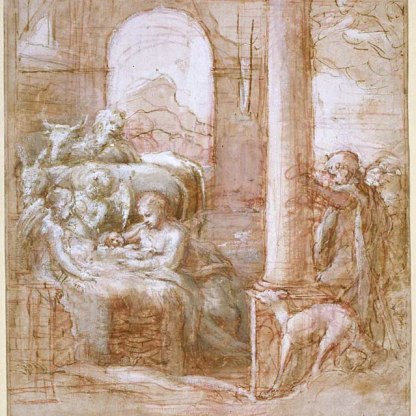

Study for a Figure of Christ

Painter, sculptor, architect and poet: by the time he made this drawing, Michelangelo had mastered every one of the arts to which he had applied himself. Born in Florence, he had as a youth trained in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio and enjoyed the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici. He had travelled throughout Italy, working for a succession of popes and noblemen, and created what are still considered by many to be the greatest art works of the Italian Renaissance: the statue of David in Florence, the painted ceiling of the Vatican's Sistine Chapel, and the church of St Peter's in Rome. By the time he was thirty, it had been said of him that he was 'unique in Italy, perhaps even the universe', and in his own lifetime he was hailed as 'divine'. On the right is a portrait medal of Michelangelo from the Fitzwilliam, made by his contemporary Leone Leoni.

In 1554, perhaps around the time he made this drawing, Michelangelo wrote a sonnet which he sent to his friend and ardent admirer, Giorgio Vasari. It included the following lines:

There's no painting or sculpture now that quiets / The soul that's pointed towards that holy Love / That on the cross opened Its arms to take us.

As this verse and the sombre tone of this drawing suggest, the increasingly religious, melancholic Michelangelo was in the 1550s, with most of his friends and family dead, acutely aware of his own mortality. The man who had above all striven to show the human body in all its nobility and power, was now as much as ever concerned with the soul.

Michelangelo was a prolific, passionate and brilliant draughtsman. He believed, with Vasari, that disegno – 'drawing' – was 'the fountain and body of painting and sculpture and architecture, and the root of all sciences'. This sketch demonstrates the brilliance of his late draughtsmanship. The black chalk is so softly applied that the figure of Christ almost seem to emerge from the paper rather than simply rest upon it. The facial features are scarcely delineated, yet this very lack of focus creates a haunting impression.

Within the figure of Christ there are no sharp lines, as there are in the studies of hands on the left of the page (detail, left). The depth and sense of motion is suggested by the artist's gentle rubbing of the chalk into the surface of the paper to create varying degrees of light and shade. Look at the subtle gradations of tone on the triangle of drapery half way down Christ's body (detail, right).

Michelangelo clearly worked and reworked Christ's outstretched arm several times, in an effort to find the most appropriate and expressive angle. The resultant blurring gives a sense of motion to the figure, a feeling that he is gesturing.

This was once thought to be a preparatory study for a type of picture known as a Noli me tangere – Latin for 'Do not touch me'. The title is given to images that depict the tearful Mary Magdelene approaching the risen Christ. The phrase comes from the words used at John 20, 17: 'Touch me not. For I have not yet ascended to my father.' A Noli me tangere, from a fifteenth-century French manuscript in the Fitzwilliam, can be seen, left [MS.22.f.90].

The drawing is now, however, thought to be a preparatory sketch for Christ Taking Leave of his Mother. It is probably related to a larger cartoon – a scale drawing for a fresco – that is recorded as having been in Michelangelo's house when he died. This had been begun for Cardinal Giovanni Morone, the papal legate to Germany in 1555, who was arrested for heresy and imprisoned on his return to Rome in 1557. Morone's German connection might explain the choice of subject matter, which is unusual in Italian art, but relatively common in northern Europe.

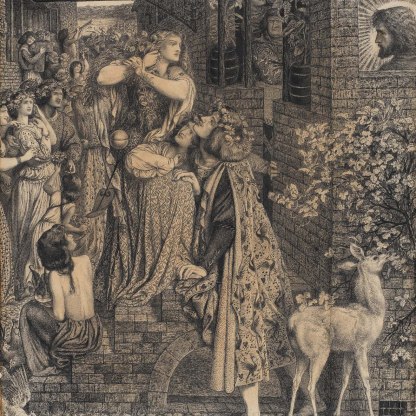

Not recorded in the Gospels, the poignant episode is imagined in medieval writings, including those of the twelfth-century British mystic Margery Kempe. It is the first in the series of events that lead up to Crucifixion. Christ bids his mother farewell at Bethany, before riding triumphantly into Jerusalem, where he is arrested and executed.

A woodcut [36.1.17a] by the German artist Albrecht Dürer, a contemporary with whose work Michelangelo was familiar, suggests how the finished picture might have been intended to look. Christ stands gesturing with his right hand towards his mother, who has collapsed in grief to the ground beside him.

It is a sombre tale, and was perhaps suited to the ageing artist who, like his subject here, was conscious of his own impending death.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Filippo Buonarroti; J.B.J. Wicar; Sir Thomas Lawrence (Lugt 2445); Samuel Woodburn, his sale, Christie's, 4 June 1860, lot 107, bt. Murray; R.P. Roupell (Lugt 2234), his sale, Christie's, 12 July 1887, lot 725, bt. Robinson; Sir J.C. Robinson (Lugt 1433), his sale, Christie's, 13 May 1902, lot 213, bt. P. & D. Colnaghi for G.T. Clough

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1913

Maker(s)

- Michelangelo Buonarroti Draughtsman

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordOther highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…