The Great Church at Haarlem

So striking, so spacious ... [here] the city’s authority is established: the proud palace, the great vast church, the markets of fish and meat.

In this extract from a 1628 poem in praise of Haarlem, Samuel Ampzing describes the experience of standing in city's marketplace. ‘The proud palace’ that he refers to is the Stadhuis (Town Hall), the portico of which the viewer is placed under in Gerrit Berckheyde’s fine cityscape. Though the portico itself has been removed, the view today has changed remarkably little since Ampzing and Berckheyde celebrated it.

But while being a recognisable and realistic depiction of the heart of Haarlem, Berckheyde’s native city, the viewpoint is contrived to highlight the symbolic value of the buildings. Three sturdy classical stone columns frame our field of vision and, as we look out across the square, we are made aware of three metaphorical pillars upon which the Dutch state, recently liberated from Spanish rule, rested: democracy, free trade and Protestantism.

Political independence and the rule of law are represented by the portico itself. Built in 1633 onto the front of the fourteenth-century Town Hall, it supported a balcony from which judicial decisions were announced. The paper notices stuck to the pillars are public announcements – the printed evidence of democracy and open government. Close to us three boys are absorbed in a game under the protective shadow of the building.

Directly across the cobbles stretches a low grey roof which shelters the stalls of the fish market, emblematic of free trade and Holland’s mastery of the sea. Here the men of the state – the burghers – conduct their business and confer in small groups. These are members of the newly powerful middle class in Holland to whom Berckheyde probably looked for patronage.

As we look across the square, there is a strong sense of aspiration and order. From left to right the buildings send spires and towers soaring towards heaven.

The sun casts sharp clean shadows that emphasise and complement the diagonal and perpendicular lines of the architecture.

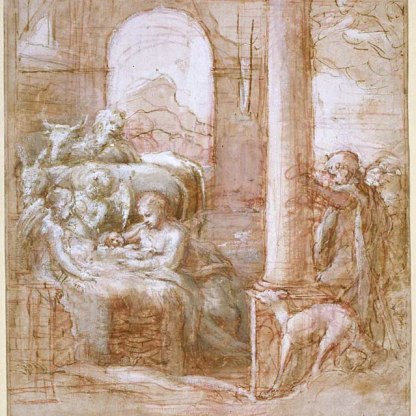

Finally, our eyes are led up to the ornate, fifty-foot-high steeple of the Groote Kerk - Great Church - St Bavo’s cathedral, the spiritual heart of the city. This gothic giant was completed in 1550 and dedicated to a hermit saint from Brabant in the Netherlands. It was a favourite subject of Berckheyde, and he painted the church more than thirty times in his career. Many other artists included it in their compositions. It appears, for example, in a seventeenth-century drawing in the Fitzwilliam, right [913], that has been attributed to the draughtsman Roelandt Roghman.

Samuel Ampzing summed up the pride felt in Haarlem for St Bavo’s:

This is that big barrel, praised in the whole country,

Such a beautiful and daring building as ever a church was made.

A credit to the town, a miracle of the country,

And almost a greater work than any made by human hands ...

Who ever saw more solid work, hewn as if out of rock;

So elegant too! Oh, pearl of buildings!

Where to find its equal? Wherever you go,

No tower exists like this on our church.

Aelbert Cuyp defined Dutch seventeenth-century achievement through its livestock and its landscape [PD.115-1975].

Gerrit Berckheyde does the same through its civic and spiritual activities and its architecture. This view of Haarlem forms a pair with an equally impressive view of the Town Hall in Amsterdam [47], also in the Fitzwilliam.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

J. Witsen; sold Amsterdam, Terwen-de Bosch, 16 August 1790 (7), bt. Coclers, (with No. 44); both anon. sale, Amsterdam, Yver, 14 August 1793 (8), both bt. J. Spruyt; both with J. Smith, London

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1816

Dating

Pendant to No. 44.

- 1670s

- Production date: AD 1674

Maker(s)

- Berckheyde, Gerrit Adriaensz. Painter

Note

Pendant to No. 44.

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…