The Royal Academy

Gentlemen, an Academy in which the Polite Arts may be regularly cultivated, is at last opened among us by Royal Munificence. This must appear an event in the highest degree interesting, not only to the Artists, but to the whole nation.

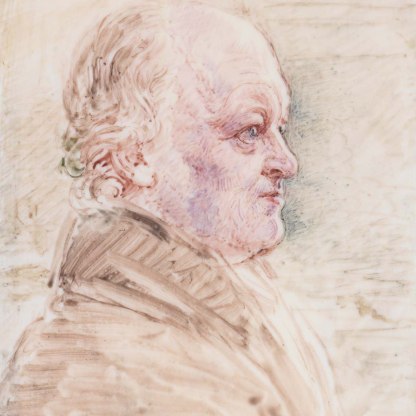

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse I, 2 January 1769

The monarch to whom Sir Joshua Reynolds gave thanks in this, his opening address as President of the newly formed Royal Academy of Arts, was George III (reigned 1760–1820). But, as Reynolds' 'at last' suggests, this was a belated act of enlightenment. London was one of the last major cities in Europe to establish an official, public Academy of Arts, although attempts had been made with varying degrees of success since 1698. Florence, by contrast, had had an Academy since 1562, when it had been headed by Michelangelo and Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici.

London's Academy distinguished itself by being set up and exclusively run by artists. It had nominal royal patronage, but the rules and regulations were written and overseen by an elected council of practising painters, sculptors and architects. It supported itself financially, chiefly through sales from its annual exhibition. For the first time in England, then, the professional status of artists was officially recognised.

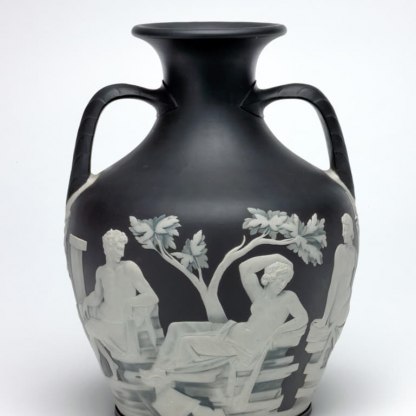

One of the organisation's chief purposes from the beginning was to teach. The Academy Schools gave full free training to young artists, who were able to draw from an extensive collection of plaster copies of antique sculptures. Life classes, with models of both sexes, were offered, although only married men or those over the age of twenty were allowed to practise on the naked ladies.

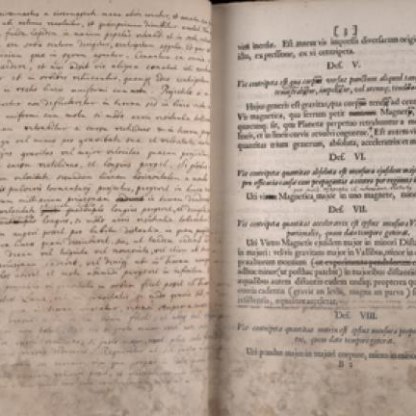

Initially the studentship at the Academy Schools lasted six years, increasing to ten by 1800. Medals were awarded to high achievers, and at the annual prize-giving ceremonies the President would deliver a 'discourse', in which the official policy of the Academy was outlined. Sir Joshua Reynolds' fifteen addresses, made between 1769 and 1790, are invaluable documents of the state of the visual arts in late eighteenth-century England.

But though the Academy provided a safe haven for a large number of artists in its early days, by the nineteenth century, the institution was coming under increasing attack. There were charges of arrogance: the Academicians, it was suggested, were so giddy with excitement at their new status that they ignored the achievements of British artists who had preceded them.

A more serious gripe, however, was with the monopoly the insitution now seemed to exercise over art in England. Many young, aspiring artists were discouraged by their failure to be accepted by the Academy, and even mature painters grew disillusioned with the establishment.

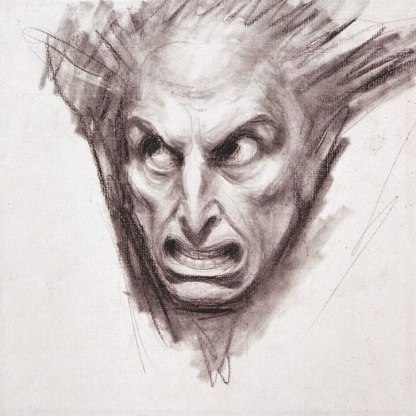

In 1816 the history painter Benjamin Robert Haydon published a frank and confrontational article, On Academies of art (more particularly the Royal Academy) and their pernicious effect on the Genius of Europe. This argued violently against the exalted power that the Academy wielded, and although his polemic was in part fuelled by his own wounded pride, Haydon's criticisms attracted support from fellow artists and politicians.

In 1809 Haydon recorded in his diary the effects, both personal and professional, that his failure to get along with the Academy had upon him:

'I lost my Patrons & sunk into a species of despair & embarrassment from which I have had occasional gleams of sunshine, but never permanent fortune ... [the Academy] threw a cloud on my whole life – embarrassments, exasperations followed.'

(He eventually committed suicide in 1846.)

The Academy was never very receptive to new movements in art. There was general hostility, for example, to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848. This reputation for retrograde conservatism, however, reached its height in 1949 when the then president, Sir Alfred Munnings, delivered an excoriating attack against modernism, describing Cezanne, Picasso and Matisse as 'foolish daubers'.

Today, the Royal Academy still functions as a school but is perhaps more widely known as a venue for large-scale exhibitions of work by Old Masters and contemporary 'foolish daubers' alike. It has shed much of its conservatism, although members of the Academy still exhibit their work in a Summer Exhibition, as they have done since 1769.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…