The Psalter

Although examples survive from as early as the eighth century, psalters reached the height of their popularity between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, when they were among the most frequently and lavishly illustrated of medieval texts.

There are two types of psalter. In one, the Psalms occur in the same numerical order as they do in the Old Testament. The letter B of the first line of the first Psalm – *Beatus vir qui non abiit ... * ('Happy is the man who walketh not ...') – is often richly decorated and takes up an entire page.

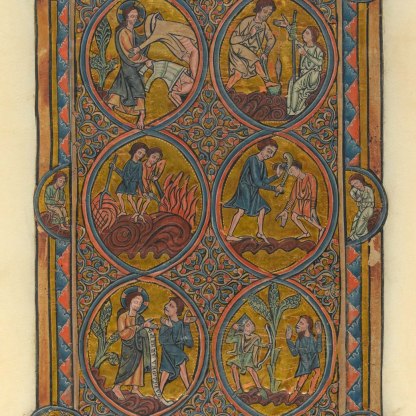

The illumination on MS.300.f.13v comes from an opulent psalter made in Paris c. 1260, probably for Isabelle of France, the sister of St Louis. In the upper circle of the B is a story from the Old Testament, II Samuel, 11, 2–17: King David spying upon Bathsheba as she bathes. Having seduced and impregnated her, David arranges for Bathsheba's husband, Uriah the Hittite, a soldier in his army, to be killed in battle. Bathsheba and David marry, a child is born but survives only a few days, and David does penance for his sin. Medieval theologians read this as a complex allegory in which David represents Christ and Bathsheba the church.

In the lower circle of the B, David's Christian credentials are made clear as we see him kneeling on the ground before Christ who appears to him floating in a mandorla – an almond-shaped, all-over body halo.

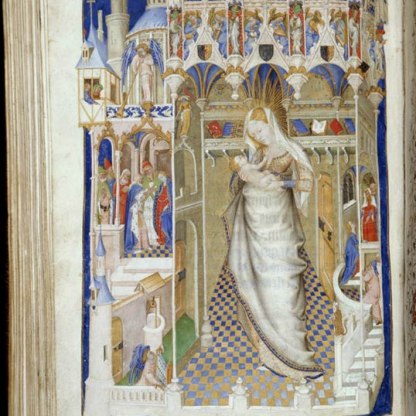

Illustrations of King David, long credited with the authorship of the Psalms, are often found at the front of psalters. The illumination MS.37-1950.f.2r, comes from a late fifteenth-century Italian psalter made for a member of the Medici family of Florence. David kneels in a superbly painted landscape, holding a stringed instrument called a psaltery. A vision of the Holy Trinity floats in the sky above him.

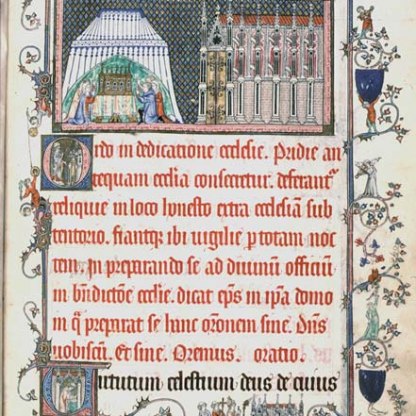

A lavishly decorated salter in the Fitzwilliam [MS.36-1950] was produced in Germany c. 1260, probably as a wedding gift to Helen, the daughter of Albert of Saxony. It includes a calendar decorated with the signs of the zodiac and the works of the months, each month accompanied by a picture of one of the twelve Apostles.

The image above shows folio 1V for January. A man is shown warming his feet by the fire, drinking and holding a gridiron over the flames. Down the side of the page are illustrations appropriate to the feast days of the month: the Circumcision of Christ, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Adoration of the Magi.

On the facing page [folio 2r] we see St Peter holding the key that identifies him in art – a reference to Christ’s words to him in the Gospel of Matthew, 16, 19: 'I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven.' He also holds a scroll that reads *Credo in Deum Patrem ... * ('I believe in God the Father ...'), the opening words of the Apostles’ Creed. Beside him Christ stands between two angels. The figure of Aquarius pours water from his jug and various saints are depicted down the left-hand column.

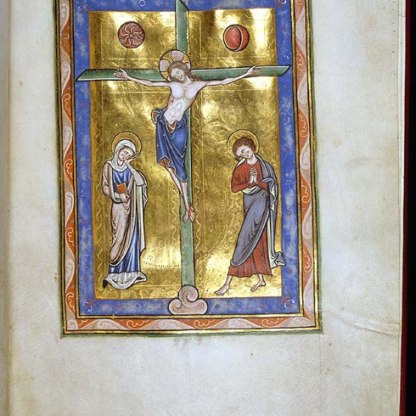

Before the Psalms begin in this volume, there are eight full-page miniatures depicting the life of Christ. A further twenty appear throughout the book. On the left [folio 22r], Christ is depicted driving the money-lenders from the temple, shortly before his arrest.

This is a de luxe manuscript and is unusual in having an illustration for each of the 150 Psalms. On folio 66v, left, David is shown kneeling, as he is threatened by two warriors, illustrating the opening of Psalm 58, where he prays, 'Deliver me from mine enemies, O my God: defend me from them that rise up against me.'

Since the Psalms played so central a role in monastic and ecclesiastical life, special liturgical psalters were also produced. In these books the Psalms occur in the order in which they were recited in the Divine Office – the collection of prayers and holy readings that priests and monks were obliged to recite daily. St Benedict, the father of Western monasticism, left clear rules about the reading of all 150 Psalms within a week, and this became the standard monastic practice. But by the twelfth century, this type of psalter was as likely to be used by a pious lay person for private prayer as by a member of a holy order.

Psalters also often contained other Old Testament readings, the creed, and other prayers.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…