The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

When the brain is hurt by an accident, or the mind disordered by dreams or sickness, the fancy is overrun with wild dismal ideas, and terrified with a thousand hideous monsters of its own framing.

Joseph Addison, 'On the Pleasures of the Imagination', The Spectator, 3 July 1712

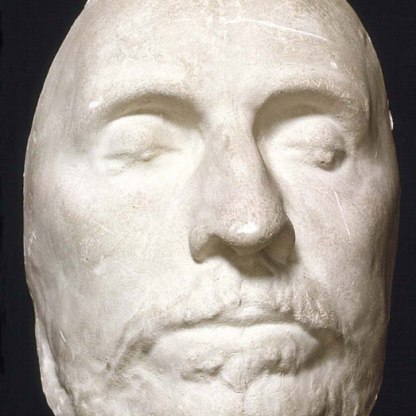

In the 1790s, middle-aged, deaf and weakened by a serious illness, the Spanish artist Goya [P.1-1986.pl1], began producing what is generally regarded as his most important work. His talents as a portrait painter were already recognised, but it was only after his illness that his imagination truly came to the fore. As the above quotation from the English essayist Joseph Addison and the imagery of this print both suggest, suffering has a tendency to unlock the darker parts of the human mind.

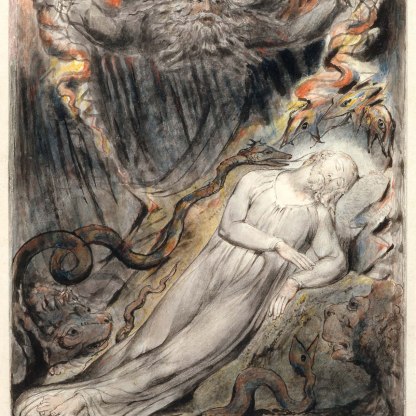

'The Sleep of Reason Produces monsters' is the 43rd plate from an album of prints that Goya entitled Los Caprichos ('The Fantasies'). A series of satirical images, their originality is stunning. At once humourous and macabre, some puzzle the viewer while others are unrelentingly forthright. The second plate [P.1-1986.pl2], shows a blindfolded woman led by the hand and accompanied by four grotesque, costumed figures, two of them scarcely human. She seems to be harangued by a crowd. Beneath this puzzling image Goya has written a caption that translates as 'They say yes and give her hand to the first comer.' It does little to clarify the image.

Goya had worked on Los Caprichos from 1793 to 1798, finally publishing them at his own expense in 1799. But, only days after going on sale, they were withdrawn, under pressure, it is thought, from the Spanish Inquisition. The plate [P.1-1986.pl24], shows a victim of the Inquisition, and it is clear where Goya's sympathies lie.

In plate 43 a man lies slumped over a desk, his pen cast aside, his face covered by his hands. On the front of the desk is written 'El sueño de la razon produce monstruos' ('The sleep of reason produces monsters'). Behind the man we see the literal truth of this. Owls flap their wings and shriek. One of them holds a crayon-holder mockingly towards him. Behind him are two lynx-like animals: one lying on the ground looking up at him, another crouching over his back, eyes shining in the gloom, staring directly at the viewer.

In the background, the silhouettes of a flock of huge bats swarm towards the scene. It is hard to think of a more vivid or universally recognisable image of delirium.

Coming just over halfway through the album, this plate serves as a kind of gateway into the supernatural. The prostitutes and pimps, drunks and monks, the asses and apes [P.1-1986.pl41], that populate the first 42 plates, give way to more sinister, darker creatures [P.1-1986.pl69]: witches, hobgoblins, phantoms and many more owls, cats and bats.

While 'The sleep of reason...' appears in the middle of the album, Los Caprichos as a whole stands at the pivot of two centuries and more broadly at a turning point between two contrasting artistic outlooks. The eighteenth century, 'the Age of Reason', had seen the dominance of Classicism, defined by a sense of order, proportion, restraint. The latter years of the century saw the rise of Romanticism, a wilder aesthetic in which the imagination came to the fore and which came to dominate art in the nineteenth century.

Which side is Goya on? Is his brain-sickly protagonist here a victim to be pitied, or is he to be admired as a kind of martyr to the greater cause of art? At around the time of the publication of Los Caprichos, European artists and writers began looking to their dreams for inspiration. In 1798 Samuel Taylor Coleridge had written his poem 'Kubla Khan, or a Vision in a Dream', under the influence of opium. The painter Henry Fuseli, an exact contemporary of Goya, is said to have eaten raw meat at bedtime to deliberately unsettle his sleep.

But while Goya's own work clearly contrasts with the balance and orderliness of much eighteenth-century art, he is not here entirely championing the irrational. One copy of Los Caprichos has captions inscribed beneath each picture, which may reflect Goya's own thoughts. That under plate 43 translates as follows:

Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of all arts and the source of their wonders.

Imagination and reason must unite to produce the best art. Neither quality must be absent. This kind of duality can be seen to have prevailed in Goya's long professional life. Over the next thirty years the artist operated as the official portrait painter to the Spanish establishment, while remaining one of its most subversive critics.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Book

Enriqueta Harris collection

Legal notes

From the Gow Fund with the aid of the Regional Fund administered by the Victoria & Albert Museum on behalf of the Museums and Galleries Commission

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bought

- Dates: 1986

Dating

80 plates and 6 pages of manuscript notes, bound in early 19th century (German binding ?)

First edition with manuscript explanations based on the Prado explanation sheets, with attempts to identify particular people, etc. , derived from the Alaya manuscript that was published by El Conde de la Vinanza, in "Goya, su tiempo, su vida y sus obras" (Madrid, 1887, pp. 327-359)

- 1790s

- Production date: AD 1799

Maker(s)

- Goya y Lucientes, Francisco José de Printmaker

Note

80 plates and 6 pages of manuscript notes, bound in early 19th century (German binding ?)

First edition with manuscript explanations based on the Prado explanation sheets, with attempts to identify particular people, etc. , derived from the Alaya manuscript that was published by El Conde de la Vinanza, in "Goya, su tiempo, su vida y sus obras" (Madrid, 1887, pp. 327-359)

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…