The Braddyll Family

Painting of old was surely well designed

To keep the features of the dead in mind,

But this great rascal has reversed the plan,

And made the pictures die before the man.

Sir Walter Blackett

These lines, written by a disgruntled client, criticise Sir Joshua Reynolds' use of unstable materials in his work. It may surprise us when we look at The Braddyll Family to learn that many of his portraits, such Mrs Angelo in the Fitzwilliam, [1775], did indeed fade or crack long before the people they represented had passed away. For this group portrait is a finely preserved image, the colours clear and clean.

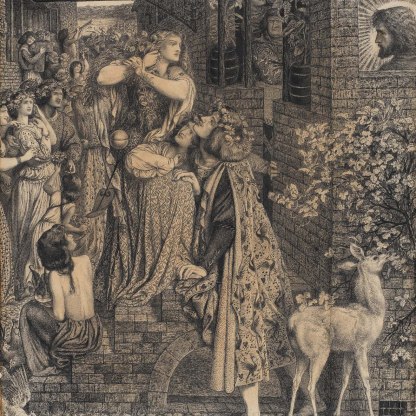

In fact the preservation of the paint is in keeping with the general sense of stability and permanence that was surely intended here. There is a stronger motive behind this portrait than a simple desire to keep of 'the features of the dead in mind'. The Braddyll Family was painted in 1789, the year of the French Revolution, when the authority of France's ruling class was violently challenged and overthrown. This proud aristocratic English family stands defiantly in the face of such upheavals.

Behind his wife, in a fine scarlet frock-coat that opens to reveal a still more splendid waistcoat, Wilson Gale-Braddyll, Member of Parliament and Groom to the Bedchamber of the Prince of Wales, stares out at the viewer. Reynolds depicts a proud, serious face.

One is reminded more of the cold, uncompromising gaze of Van Dyck's Archbishop Laud in the Fitzwilliam [2043], painted 150 years earlier, than of the poetical features of the earl of Northampton in Pompeo Batoni's 1758 portrait [PD.4-1950]. An air of authority is more important here than the celebration of any good looks, and Wilson's character is defined more by the things around him – his family and land – than by any facial expression.

His right arm rests assertively upon a bench behind his wife. Mr Braddyll is not a man of great physical presence – if his wife were to stand up, you sense that she would tower over him. But here he holds his back straight and his chest forward. As for his wife, Reynolds seems to have enjoyed painting her. He had portrayed her alone the previous year, when she had sat for him eleven times, and his record books tell us that she sat for him on a further eight occasions for this group portrait. In contrast, her husband and son sat only five times each. The potentially oppressive sense of formality is alleviated by the relationship between Mrs Braddyll and her spaniel. Jane gently fondles her pet's ear, as he sits obediently on her lap.

Mrs Braddyll looks towards her son Thomas who, slightly aloof from his parents, leans against a plinth and looks out at us.

Behind him is a copy of the Medici Vase, a celebrated Roman antiquity which was much copied in the eighteenth century. It can be seen in Gianpaolo Panini's Capriccio of Roman Ruins with the Pantheon in the Fitzwilliam [PD.108-1992]. Directly over Thomas' head is the carved figure of a Greek warrior. The boy would grow up to become an officer in the Coldstream Guards and serve England in the Napoleonic wars. Is there a hint here of the martial aspirations his family had for him?

The parklands of many European country estates were decorated with copies of antiquities like the Medici Vase. And behind Wilson Braddyll's four-square, frontal stance, behind his even, unflinching gaze, it is not difficult to percieve a defiant belief in the English class system, based as it was upon land-ownership and succession.

This family is a solid unit: the members form a pyramid of stability. Wilson's estate stretches out behind him, and the way that the two males' bent left arms echo one another hints that, when the time is right, the future soldier Thomas will take his place as landowner and head of another generation of Braddylls.

Joshua Reynolds was born in a small Devon town, the son of a schoolmaster. By the time this painting was made, however, he had been knighted, had amassed a considerable fortune and owned significant properties in London. He was the first President of the Royal Academy in London, and a gentlemen member of the aristocratic Society of Dilettanti. He was friendly with and painted many of the most powerful men of his day. An unfinished portrait in the Fitzwilliam [653] from c. 1766 showing the then Prime Minister of England, Lord Rockingham, with the politician Edmund Burke. In short, Reynolds was a fully accepted member of the establishment that he was so frequently called upon to portray. The Braddyll Family was probably the last portrait he painted before blindness put an end to his career.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Lt-Col. Thomas Richmond-Gale-Braddyll (1776-1862); his sale, Christie's, 23 May 1846 (44), bt. Bishop; W.J. Isbell, of Stonehouse; T. Pooly Smyth, of Plymouth, by 1857; Pooly Smyth sale, Christie's, 13 June 1859 (213), bt. in; Rev. W.C. Randoph; Lionel, 2nd Lord Rothschild (d. 1937), Tring Park, by 1899; his nephew, Nathaniel, 3rd Lord Rothschild; given by him to the Lord Baldwin Fund for Refugees, sale at Christie's, 25 May 1939 (256), bt Gooden & Fox; bt. from Gooden & Fox, London, by E.E. Cook, 1939, who bequeathed his collection to the National Art Collections Fund, 1955

Legal notes

From the Ernest Edward Cook collection.

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1955

Dating

- 1780s

- Production date: AD 1789

Maker(s)

- Reynolds, Joshua Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…