Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

I must confess that upon entering the gardens, I found every sense overpaid with more than expected pleasure; the lights everywhere glimmering through the scarcely moving trees; the full-bodied concert bursting on the stillness of the night; the natural concert of the birds, in the more retired part of the grove, vying with that which was formed by art; the company gaily-dressed ... and the tables spread with various delicacies, all conspired to fill my imagination with the visionary happiness of the Arabian lawgiver [Mohammed], and lifted me into an ecstasy of admiration.

Oliver Goldsmith, The Citizen of the World, 1760

The Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith vividly evokes the experience of visiting Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens on the south bank of the Thames in the mid-eighteenth century. He may not have been entirely sincere in his flattery of the place, but, for many people, Vauxhall was the greatest of several such resorts founded in London after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

Originally called the New Spring Gardens, the site was laid out in 1661, a simple network of pathways through trees, with arbours where the visitor could eat supper. Early on in its history, however, Vauxhall became known for less innocent pastimes. Samuel Pepys records a visit there in 1668 in 'the company of Harry Killigrew, a rogue newly come back from France, and young Newport and others, as very rogues as any in the town, who were ready to take hold of any woman that came by them'.

In 1728 the Gardens were leased to Jonathan Tyers, under whose management they became a major feature of London's social scene. In 1732 he marked the opening of the re-landscaped gardens with a magnificent Ridotto al fresco, an Italian-style masked ball.

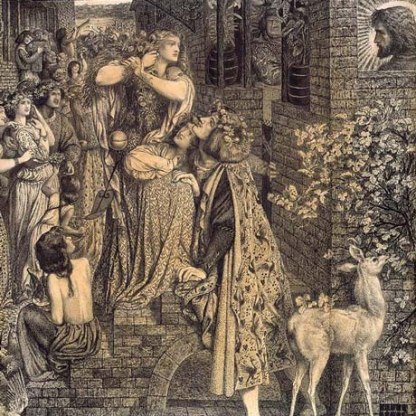

Music was central to Tyers' revival, and the heart of his pleasure park was a round bandstand known as the Orchestra, where works by Handel, Haydn, Hook and other great composers of the day were performed. It was hoped that the soothing power of this music would lead to more civilised conduct among the trees and shrubs: as Orpheus' lyre had charmed the animals, so might Handel's music tame the bestial side of London man. But Vauxhall's reputation as a venue for illicit delights remained.

A comic poem entitled A Trip to Vaux-hall: Or A General SATYR on the TIMES was published in 1737 by one 'Hercules Mac-Sturdy, of the County of Tiperary, Esq.'. In it, the poet strolls around the gardens noting the qualities of people. Most of them, he finds, are wanting in moral fibre:

The doting Cit here hugs his wanton Wife,

Calls her his Sweeting Fubsey, Duck and Life,

Nor grudges Ham, tho' fourteen Pence an Ounce,

Whilst Horns she's making o'er the Cuckold's Sconce:

But to the Captain gives such am'rous Leers,

As shew her Heart is his, and not her Dear's.

Tho' to this Grocer but two Winters wed,

Three 'Prentices at home have shar'd his Bed;

Abroad Six honest Countrymen of mine,

And of the Army Blades some thirty-nine.

A rather more sublime poetical testament to the erotically charged atmosphere at Vauxhall is found in Sonnet: To a Lady Seen for a Few Moments at Vauxhall, by John Keats.

Roubiliac's statue of Handel was perhaps the most important work of art commissioned by Tyers, and it became the symbol of the gardens as a whole, its image reproduced on entrance tickets and on the crockery used in the supper boxes. There was, however, plenty of other original artwork on display. William Hogarth is thought to have advised on the decorative scheme, while his friend Francis Hayman provided paintings for the supper boxes.

Tyers died in 1767, but the gardens stayed in the family until his great-grandson, a clergyman, put them up for sale in 1818. After Tyers' death, however, spectacle gradually replaced sophistication in the entertainment provided. Fireworks were introduced in 1798 and balloon ascents in 1802. In 1814, a basin for recreating sea-battles was dug. In 1816, Madame Saqui, the celebrated tightrope-walker, first appeared, bringing in her wake a trail of acrobats, Indian jugglers and vaudeville performers. Trees were cut down to accommodate ever more garish attractions until, on 25 July 1859, the final evening's fun was had. Soon afterwards, the remaining trees were felled and the site was taken over by property developers.

Tyers Street and Jonathan Street still survive in the area today, the only legacy of this infamous eighteenth-century pleasure resort.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…