Reading

The figure of the reader, particularly the female reader, has been a common one in art since medieval times.

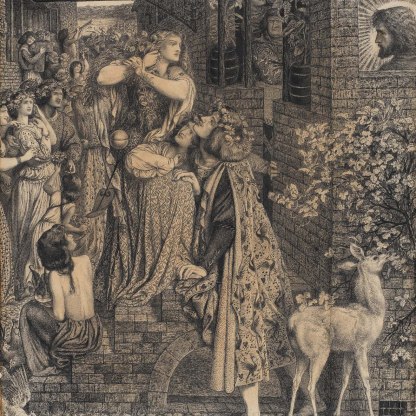

The classic female reader is the Virgin Mary in Annunciation scenes. In an early sixteenth-century Flemish Annunciation in the Fitzwilliam [98], a book is open on a lectern in front of Mary, from which she turns to face the Archangel Gabriel. In Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s 1861 Annunciation [1574], a tiny volume also lies open upon her knee. Sometimes the text that Mary reads is legible as a prophecy of Christ’s birth from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah.

In Hendrik Goltzius’ late sixteenth-century drawing of Mary Magdalene in the wilderness [PD.164-1963], there is an open book beside the saint’s alabaster jar, her crucifix and her skull: all four objects emblematic of her piety and penitence.

A male counterpart to the penitent Magdalene can be seen in Alessandro Allori’s 1587 painting St. Benedict in the Wilderness [PD.19-1996]. Here the young saint lies on a bed of brambles, intently reading to keep his mind of the demon women who leer behind him.

In a charming late fifteenth-century depiction of the Virgin and Child with the Infant St John by Pinturicchio [119], it is Christ himself who is precociously engrossed in a book.

The vain, bejewelled beauty in a seventeenth-century painting by Paulus Moreelse [PD.32-1968] is the very opposite of these devout readers. The work has been interpreted as an 'Allegory of Profane Love', and in the book that lies open on the girl's dressing table, we read a Latin couplet meaning:

'The desire of the flesh [lascivia] does not live for itself but for Venus. To her she offers gold and jewels and all riches.'

It is illustrated by an image of an old woman doing obeisance before a statue of the goddess of love.

The appearance of books in pictures can suggest intellectual distinction on the part of those portrayed. The book-lined shelves in the background of the portrait of the novelist Thomas Hardy by Augustus John allude to both the source of his fame and his intellect [1116].

In the portrait of the seventh earl of Northampton by the Roman painter Pompeo Batoni [PD.4-1950], the young aristocrat’s love of learning is implied by the volumes on the table in front of him. He is overlooked by the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva.

Other images of readers have less precise meanings. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s study of Lizzie Siddall [2155], has a domestic feel to it, as though the artist, seeing his wife reading, has taken chance to make an affectionate and intimate sketch. Reading of course also gives the model something to do while she is being immortalised.

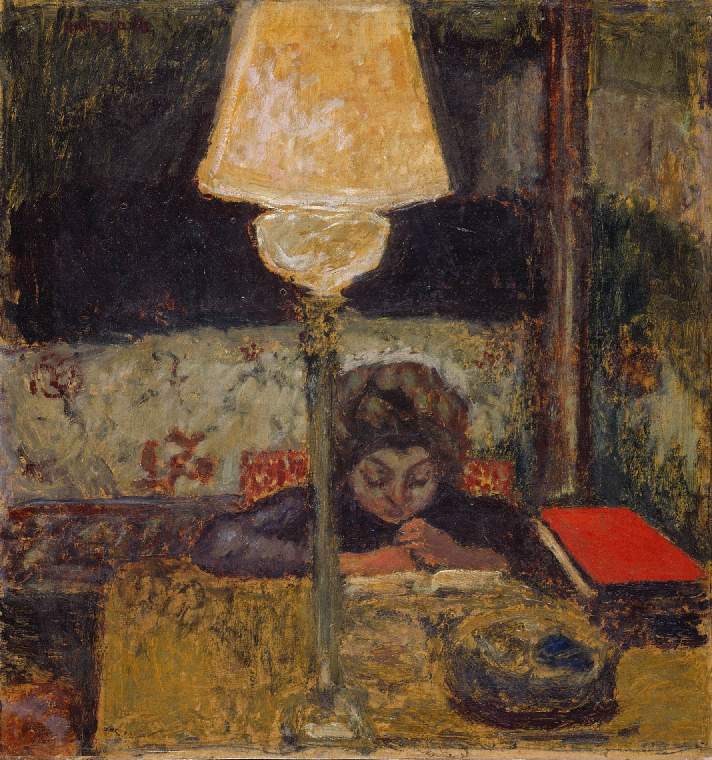

Pierre Bonnard’s late nineteenth-century painting The Oil Lamp, below [PD.28-1998], likewise suggests a private moment, spontaneously caught by the artist.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…