The Crucifixion

[It] is the most tragic of all themes, and yet inherent in it is the promise of salvation. It is the symbol of the precarious balanced moment, the hair’s-breadth between black and white. It is that moment when the sky seems superbly blue – and when one feels it is only blue in that superb way because at any moment it could be black – there is the other side of the mirror – and on that point of balance one may fall into the great gloom or rise to great happiness ...

The English painter Graham Sutherland wrote these words in the mid-twentieth century, in the wake of the Second World War. But he was talking of a theme that has been treated by Western artists since at least the fifth century CE: the death of Christ upon a cross.

The earliest Christians did not depict Christ’s death, perhaps because execution on a cross was shameful, a punishment usually reserved for slaves and the lowest criminals. In the earliest surviving narrative depiction of the Crucifixion, on a panel from an ivory casket now in the British Museum, Christ is shown attached to the cross wide-eyed and alive, his arms spread more in triumph than surrender. Beside him the limp and unmistakeably dead figure of Judas hangs from a tree.

In a striking illumination from a fifteenth-century Italian missal in the Fitzwilliam [Marlay cutting It.28], Christ hangs in darkness, utterly alone. The cross – the wood of which is painstakingly rendered here – is mounted into the summit of a rocky hill: Calvary, outside Jerusalem, the walls of which can just be made out in the background. The pallor of Christ’s body, the angle of his head and his closed eyes tell us that he is dead. But around this main picture are brighlty lit subsidiary scenes that show the miraculous, life-affirming aftermath of his execution.

Directly below the central scene, Christ is shown harrowing Hell – releasing from Purgatory the souls of those who had died before his coming. This event traditionally took place between his death and his Resurrection – which we see taking place on the left of the page. Here Christ floats triumphantly above the open tomb, as three dumbstruck soldiers look on. He carries a banner bearing a red cross: the instrument of his torture has become the symbol of his triumph. On the right side of the page he is shown ascending into Heaven.

Nailed above Christ’s head in the central picture is a sign bearing the letters: INRI. This is the titulus – the headboard mentioned in the Gospel of John, 19, 19 – that was put on the cross by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea under whose authority Christ was executed. INRI stands for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum – Jesus Christ, King of the Jews.

The full Latin inscription can be seen on a late thirteenth-century panel painting from Umbria in the Fitzwilliam [564]. Again Christ is shown dead. His eyes are closed, his head hangs limp and you can clearly see the wound in his side where he was pierced by a lance to make sure of his death. He hangs here upon an unusual Y-shaped cross.

On either side stand the Virgin Mary and the apostle John. The two are often shown as witnesses to the Crucifixion, following a passage in John’s Gospel, 19, 26–7:

When Jesus therefore saw his mother, with the disciple standing by, whom he loved, he saith unto his mother, Woman, behold thy son!

Then saith he to the disciple, Behold thy mother! And from that hour the disciple took her unto his own home.

Above them hover two weeping angels.

At the bottom of the cross, scarcely visible today, is the much abraded figure of Mary Magdalene. She is more clearly visible on a slightly later panel painting in the Fitzwilliam by the Master of Verucchio, who was active in Rimini c. 1320. You can see this on [PD.8-1955]. With long blonde hair and a bright scarlet cloak, the reformed prostitute gazes up at the dead Christ. Kneeling opposite is St Francis of Assisi, the great Italian theologian and founder of the Franciscan order. He is shown bearing the stigmata – the wounds that Christ suffered – on his own hands.

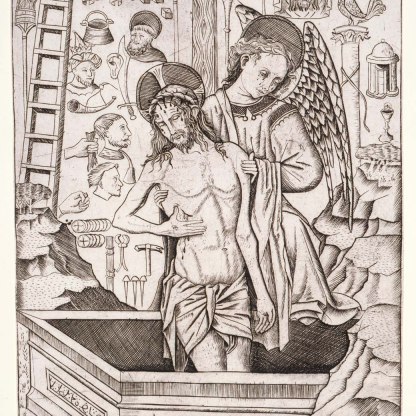

The cross depicted here has clearly been cut from a living tree – the stubs of roughly hewn branches can be seen. Christ is sometimes shown crucified upon a tree that still bears leaves and flowers. This is a reference to the arbor vitae – the tree of life. The thirteenth-century Franciscan theologian St Bonaventura taught that the tree of knowledge from the Garden of Eden was brought to life again by Christ’s blood.

Another reminder of the Garden or Eden often found in Crucifixion scenes is the skull of Adam at the foot of the cross. It can clearly be seen in Albrecht Dürer’s 1511 print, [1876.12.16-84]. This highlights the redemption bought about by Christ’s death: his blood literally washes away the sins of Adam and the generations that followed him.

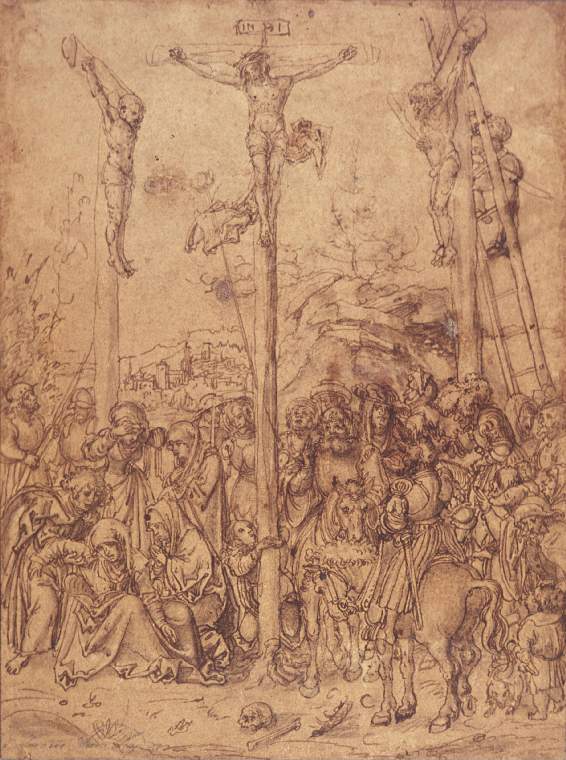

The Virgin Mary, John and Mary Magdalene are shown in a beautiful leaf from a Flemish Book of Hours, c.1520, in the Fitzwilliam [MS.294a]. It is a particularly affecting image – the faces of the onlookers are masks of grief, their eyes red from weeping. Christ is elevated high above them in this image, flanked by the two thieves. These are common figures in Crucifixion scenes, first appearing in the sixth century on a wooden door panel in the Church of Santa Sabina in Rome. The thieves are often crucified in slightly different ways to Christ: here they are tied rather than nailed to their crosses, which are much more roughly hewn than that in the centre.

According to the Gospel of Luke, 23, 43, one of the thieves mocked Christ on the cross, while the other defended him and asked for his blessing: 'And Jesus said unto him, Verily I say unto thee, To day shalt thou be with me in paradise.'

Artists often distinguish between the good thief, called Dismas in the medieval tradition, who appears on Christ’s right, and the bad thief, Gestas, on his left. Though there is physically little to tell between the two in the Flemish manuscript illumination, the thief on Christ’s right gazes up to the sky, while the one on his left has his head hung towards the earth.

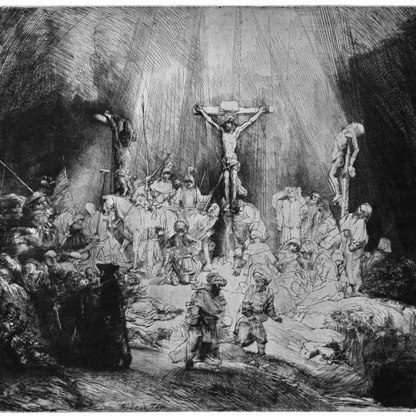

By the fourteenth century, artists were including more and more figures in Crucifixion scenes. 2929 is an early sixteenth-century drawing in the Fitzwilliam by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a preparatory study for a large painting now in Copenhagen. A significant crowd, including children, has assembled beneath the cross. At the left the Virgin Mary has collapsed and is being supported by the apostle John.

A wine-soaked sponge on a stick is raised towards Christ, an event mentioned in all four Gospels. We cannot discern who is offering the sponge here, but medieval legend named the sponge-bearer Stephaton. He is often paired in art with Longinus, the carrier of the lance that pierced Christ's side. The blood and water that emerged from the resulting wound are said to have fallen into Longinus' eye, thus curing him of a lifelong affliction. Longinus is also identified with the centurion who acknowledged Christ as the Son of God at the moment of his death.

A painting from 1800 by William Blake in the Fitzwilliam offers an unusual view of the Crucifixion, below [PD.30-1949]. Here we see the three crosses from behind, with only parts of Christ’s outstretched upper arms visible against the red glow of the eclipsed sun. In the foreground, the Roman soldiers roll dice for Christ’s tunic. Blake’s painting was inspired by a work by the French painter Nicholas Poussin.

The gambling soldiers appear in the foreground of an illumination from a fifteenth-century French manuscript in the Fitzwilliam [MS.62.f.199r]. Two distinct episodes from the Crucifixion narrative are depicted here. In the foreground, six executioners attach Christ to the cross, while further back we see him dead, Stephaton and Longinus extending the sponge and lance towards him. Above it all, God the Father, radiant, looks down from heaven upon the violent, earthly death of his Son.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…