The Labours of Herakles

I shall sing of Zeus’ son, Herakles, noblest of mortals,

Born at Thebes, city of lovely dances,

Of the union of Alkmene with Zeus, Lord of the Dark Clouds.

In the past he wandered endlessly over the boundless earth and sea

On missions ordered by Lord Eurystheus,

And he committed many reckless deeds and himself endured many.

But now he joyously dwells in his beautiful abode

On snowy Olympos with fair-ankled Hebe as his spouse.

Hail, O Lord and son of Zeus! Grant me virtue and happiness.

The Homeric Hymn to Herakles, translated by Apostolos N. Athanassakis

This hymn of praise and petition to Herakles dates from the sixth century BCE. But it could have been used at almost any period of antiquity, so popular and widespread was the cult of this hero who became a god.

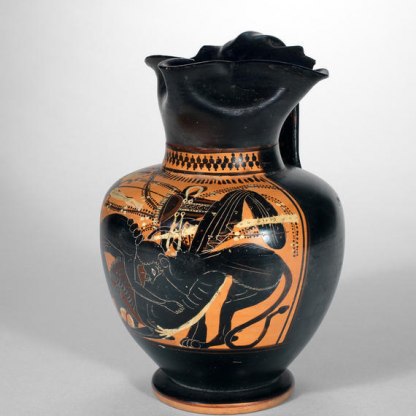

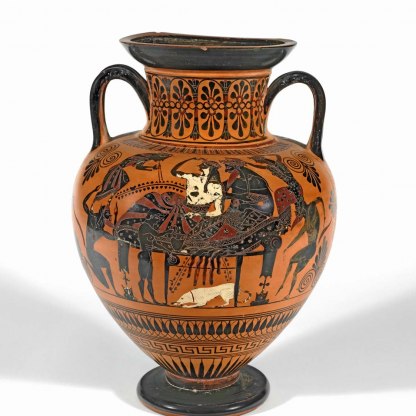

The man fighting the lion on this black-figure wine jug, made in Athens around the beginning of the fifth century BCE, is the same as the figure found on a Buddhist carving in the Fitzwilliam made in what is now northern Pakistan. The same hero appears in a design for an early seventeenth-century fresco by Annibale Carracci, left, where he is asked to choose between a life of comfortable vice or hard-won virtue.

Herakles may have had quite different meanings to the viewers of these three different representations. But he is easily recognisable in art by his club, his lionskin or his beard – often all three.

Herakles is perhaps best known for the Twelve Labours that he had to perform, in atonement for killing his wife and children after Hera, the jealous wife of his father Zeus, had sent him into a fit of madness. These Labours have provided subject matter for artists and writers for millennia. The number twelve might have become the norm after the twelve carvings on the temple of Zeus at Olympia, Greece, erected in the first half of the fifth century BCE.

This seventeenth-century drawing by the Italian artist Ciro Ferri in the Fitzwilliam [PD.10-1992] is entitled An Allegory of the Labours of Heracles. The hero sits on a rock, leaning on his club. Behind him are four crowned gods, while to his right we see eight of the beasts he vanquished during his labours. They are: the Cretan Bull, the Cerynian Hind, the Horses of Diomedes, one of the Stymphalian Birds, the Erymanthian Boar, Cerberus the three-headed dog who guarded the underworld, the many-headed serpent Hydra and the Nemean Lion.

The single bull might also stand for the cattle of Geryon, a monster whose herd Herakles had to rustle, and the herd of King Augeas whose filthy stables he had to clean.

Two of the traditonal twelve labours did not involve animals. In one Herakles had to bring Eurystheus the belt of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, a fierce race of warrior women from the East. In the other he had to steal the golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides, at the very ends of the earth.

In the course of his twelve labours Herakles endured many other stern tests and fights. While searching for the Garden of the Hesperides for instance, he was challenged by the Libyan giant Antaios. The two wrestled, but Antaios was at an advantage: as a child of the earth goddess Gaia, every time he was hurled to the ground he drew strength from it. In the end Herakles lifted him into the air and crushed him to death. This battle is perhaps shown in a first–second-century CE bronze in the Fitzwilliam [GR.4.1954].

Herakles could be uncouth, and in Athenian comedy of the fifth century BCE he was often mocked for his drunkeness and lechery. Left is a third–first-century BCE bronze, apparently showing the hero reeling drunk [GR.3.1864].

But he was also praised by philosophers for his stoical acceptance of hardship. He is shown in reflective mood in a second-century BCE terracotta [GR.88a.1937], where he has exchanged his lionskin for the robes of a philosopher.

Traces of Herakles survive in the Christian tradition. Samson and David in the Old Testament both fought lions like the Greek hero. And on the late twelfth-century porch of the cathedral of St Trophimus in Arles, southern France, beneath images of Christ and the saints, are carvings of Herakles fighting the lion and carrying off the Kerkopes, two ape-like thieves who bought a rare smile to the hero’s face by laughing at his hairy, sun-blackened buttocks.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…