The Loves of Jupiter

Male or female, divine or mortal, willing or afraid: Jupiter forced himself upon many partners. His love affairs and the offspring they produced have inspired artists for centuries.

Jupiter's lawful wife was also his sister, Juno. We see them in a coin in the Fitzwilliam [McClean 7872], minted on the island of Tenedos and dating from 189 BCE. Juno bore Jupiter four children: Vulcan, the disfigured blacksmith god; Mars, the god of war; Juventas, the cup-bearer to the gods and goddess of youth; and Lucina, the goddess of childbirth.

In a print in the Fitzwilliam [39.9.60], based upon a painting by the sixteenth-century Italian artist Giulio Romano, the divine couple are shown embracing in their bedroom. The marriage however was not a conventionally happy one and if in myth Jupiter is known for his blithe lust, Juno is characterised by her bitter jealousy of the women her husband slept with and the children they bore.

The child of Jupiter to suffer most acutely from this jealousy was the Greek hero Herakles (Latin Hercules). His name literally means 'the glory of Hera', but this in no way pacified Jupiter's spouse. Herakles' mother was Alcmene, a beautiful mortal whom Jupiter seduced in the guise of her husband Amphitryon while was away at battle. We see this happening [39.9-61] in another print based upon a work by Giulio Romano. At Jupiter's command, the sun took a holiday and so the night he spent with Alcmene in fact lasted three nights and a day. Herakles, the greatest of all the Greek heroes, was born, but he was dogged all his life by the jealous anger of his father's lawful wife.

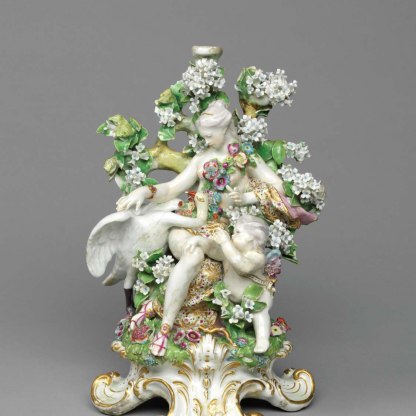

When Jupiter became enamoured of the beautiful son of King Tros, Ganymede, he swooped down as an eagle and installed him in Olympus as his cup-bearer. A bronze statue in the Fitzwilliam by Soldani shows this abduction, above [M.59-1984]. It was a popular subject in ancient Greek art too.

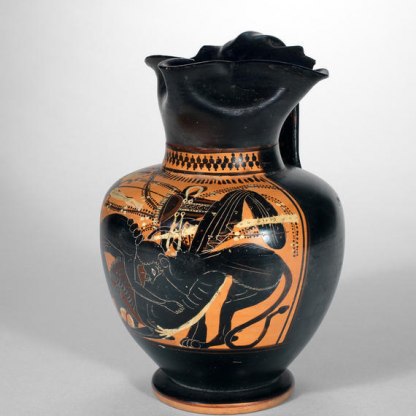

Jupiter commemorated his love for Ganymede by creating the constellation Aquarius, seen in a page from a fifteenth-century north Italian manuscript [MS.260.f.24r]. A fragment from a mid-fifth-century BCE Athenian red figure vase in the Fitzwilliam [G.P.13], which might depict Ganymede acting as a wine waiter for the Olympian gods.

The very foundation myth of Europe rests upon a love-trick by Jupiter. When he fell for Europa, the daughter of Agenor, the king of Tyre, the god took the form of a beautiful white bull. Approaching Europa and her friends as they played upon the sea shore, he enticed her to climb upon his back. He then carried her off to Crete, where she bore him the future King Minos. An attractive account of the story can be seen on a maiolica dish in the Fitzwilliam, below [C.80-1927]. More recently the abduction of Europa has been used on the Greek two-euro coin, right.

The Fitzwilliam also owns a bronze sculpture depicting this abduction by Soldani's contemporary and rival Giovanni Battista Foggini, below [M.3-1968].

Another strange and rather complex myth provides a kind of reversal of the Europa story. When Jupiter fell in love with Io, daughter of the river god Inachus, he turned her into a white heifer so that his wife would not suspect that his eye had once more roved. But Juno was not deceived, and the jealous goddess claimed the heifer as her own. She set the hundred-eyed herdsman Argos to guard Io so that she might tempt Jupiter no further. The cunning god Mercury killed Argos, however, thus releasing Io. Juno in anger sent a gadfly to sting the heifer and chase her all over the world.

She finally came to rest in Egypt where Jupiter returned her to her human form and, by merely touching her, impregnated her with a son, Epaphus. Some writers record that she was worshipped in Egypt as the goddess Isis. Epaphus has been identified with the Egyptian bull-god Apis.

A painting by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Jacob Pynas in the Fitzwilliam, below [PD.9-1977], shows Juno grumpily regarding her spouse who lies half-naked next to a heifer, his thunderbolt held lazily in his hand. A peacock – representing Argos – is leashed at Juno's feet. Jupiter's miraculous impregnation of Io is shown in a print, right, again based upon Giulio Romano. The god lays his hand upon the belly of his beloved as Juno watches from a cloud.

In Rembrandt's 1659 print, Jupiter and Antiope [AD. 12.39-159], the lust-filled god creeps up on the sleeping, naked princess in the form of a leering old satyr.

Jupiter did not even have to take on the form of a living thing to have his way. When the princess Danae was imprisoned in a brazen tower by her father, Jupiter descended as a shower of gold and impregnated her with the future hero Perseus. Left is another Giulio Romano-inspired print depicting this encounter.

Jupiter had to take all these different forms for one very good reason: his natural form was lethal. He does not seem to have used trickery to seduce the mortal princess Semele, left. Out of jealousy at their affair, however, Juno disguised herself as a mortal and, gaining Semele's confidence, persuaded her to ask Jupiter to make love to her in his natural splendour. Semele was incinerated by the lightning that accompanied the god in his pure state. But from the ashes Jupiter took the unborn child that she was carrying and placed the still-living foetus in his own thigh. In time, he gave birth to the god Bacchus.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…