The Suffering Christ

He was despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not ... But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed ...

Isaiah, 53, 3.

In this, one of the most vivid prophecies of Christ in the Old Testament, Isaiah describes a pitiful, vulnerable saviour. During the middle ages, there was an increasing emphasis upon the humanity of Christ, particularly in the events leading up to his Crucifixion. The teaching of St Francis of Assisi (c. 1182–1226), who himself miraculously suffered stigmata – the wounds of Christ – was particularly influential on this strand of medieval piety. In art, from the early middle ages and beyond, Christ is shown increasingly as a god of flesh, a divine figure who nevertheless bleeds, sheds tears of compassion, feels pain. The halo is sometimes obscured by the crown of thorns.

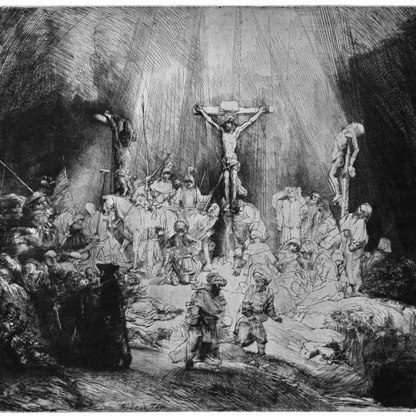

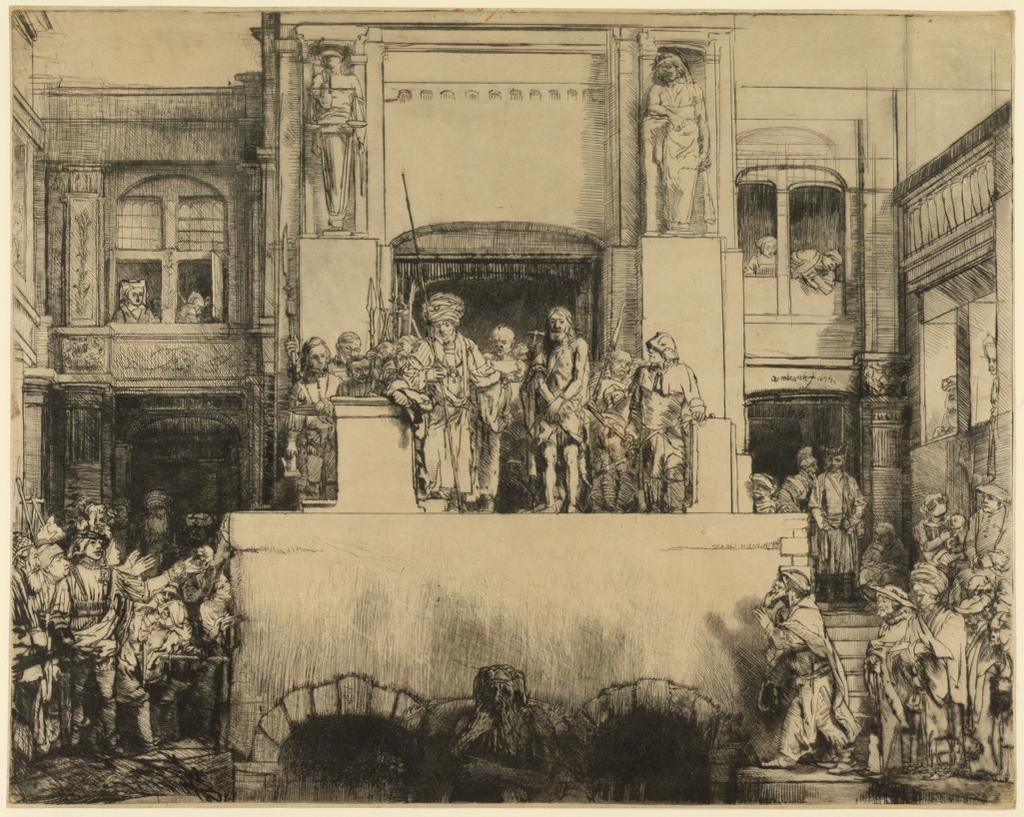

In his 1655 print, Christ presented to the people [23.K.5-130], the Dutch artist Rembrandt depicts the moment described in the Gospel of Matthew, 27, 21–3, when Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, offers the people of Jerusalem the chance to grant amnesty to either Christ or Barabbas, a common criminal.

In an earlier state of the print Rembrandt included a crowd immediately beneath the balcony upon which Pilate and his prisoners stand. But in the state illustrated here, these figures have been removed. Pilate and Christ – his hands bound – now stare directly at the viewer of the print. We are cast as the crowd who choose Barabbas over the Son of God. We are implicated in the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecy.

Having been condemned, Christ was taken away to be tortured by the Roman soldiers. A small seventeenth-century gilt-bronze group by the Roman sculptor Alessandro Algardi depicts the flagellation of Christ in a surprisingly beautiful way. The lavish gilding and overall elegance of the figures hardly seem in keeping with the brutal violence of the event. It is thought that this group might have been a gift from Augustus the Strong, king of Poland to his confessor, Alessi von Pisarni.

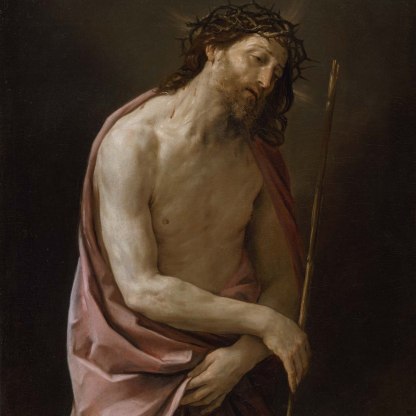

After scourging Christ, the soldiers put a crown of thorns upon his head, and wrap him in a purple robe – a cruel parody of kingship. Pilate then, according to St John’s Gospel, 19, 5–6, presents him to the people again:

Then Jesus came forth, wearing the crown of thorns and a purple robe. And Pilate saith unto them, Behold the man!

When the chief priests therefore and officers saw him, they cried out saying Crucify him, crucify him.

The Latin words that Pilate uses to introduce Christ to the crowd are Ecce Homo (‘Behold the man'). They are used as the title for a type of picture in which Christ is shown wearing his crown of thorns. He might appear alone, the wounds of the flagellation fresh upon his body, or he might be part of the narrative scene. In a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer [P.3252-R], we see him standing on a balcony, patiently receiving the abuse of the crowd beneath, the calls for his execution.

An early sixteenth-century painting in the Fitzwilliam [PD.4-1955], attributed to a Milanese artist known as the Master of the Pala Sforzesca, mixes the Ecce Homo with another picture type known as Salvator Mundi (‘Saviour of the World'). Christ wears the crown of thorns, but he also raises his hand in blessing and holds an orb topped by a cross – the sign of his heavenly kingship. The spiritual truth behind the soldiers’ mockery is shown.

Having been condemned, tortured and sentenced, Christ begins his final journey: to Calvary, the hill outside Jerusalem where the Crucifixion took place. The Hebrew name for this hill is 'Golgotha' – literally ‘the place of the skull'. This journey is also known as the Via Dolorosa (‘the Mournful Way'). The various events that take place on the Road to Calvary are called the Stations of the Cross. Originally there were seven Stations – marked by images at various places in a church. This was later increased to fourteen.

We see Christ carrying his cross towards Calvary in an anonymous early fifteenth-century British panel painting in the Fitzwilliam [707]. Blood runs down his neck from the wounds made by the thorns. A soldier bludgeons him with the handle of a mace. Another seems to be supporting him from behind, though the gesture is hardly a friendly one. In the background we see the faces of the Virgin Mary and St John. The panel is badly damaged – a victim of Reformation iconoclasm, the widespread destruction of religious images that took place in England under Henry VIII and his son, Edward VI, in the sixteenth century.

A painting by the Venetian artist Jacopo Bassano in the Fitzwilliam [M.6], dating from c. 1538, shows more completely the entourage who accompanied Christ on the Road to Calvary. Here a soldier drags him by a rope tied around his waist, while another raises a whip behind him. Christ has collapsed onto his knees but his attention is focused on his mother. She has swooned to the ground and is being helped by three other women. St John, a young man in a red robe, stands behind, in a sorrowful pose.

St John states that Christ carried the cross on his own, but the other Gospels all mention that a man called Simon, from Cyrene in Africa, was called upon to carry it for him. Artists usually showed Simon helping Christ rather than bearing the burden exclusively. Left is an early sixteenth-century Flemish wooden sculpture in the Fitzwilliam [M.7-1943]. Christ reaches out a hand to the ground to break his fall, while Simon holds up the base of the cross.

We also see Simon, old and bearded, in a late fifteenth-century woodcut by Albrecht Dürer [P.3255-R]. This is part of a Passion Cycle – a series of twelve images, in this case, which narrate the events from the Last Supper to Christ’s Resurrection.

Another bystander said to have helped Christ, as he struggled with the cross, was St Veronica. She is not mentioned in the Gospels, but Christian legend relates how she used her veil to wipe the sweat from Christ’s head, the fabric of which was then miraculously imprinted with an image of his face. A piece of cloth, known as the vernicle or sudarium, which purports to be this very veil, was kept in St Peter’s, Rome, from the eighth to the sixteenth century. The name 'Veronica' was claimed to be derived from the Latin vera icon, meaning ‘true image', though in fact it is the Latin version of the Greek name Berenice. A drawing in the Fitzwilliam shows the saint, a turbanned, rather careworn looking woman, holding up the miraculous image. This drawing is based upon a fifteenth–century painting now in Frankfurt by the Flemish artist Robert Campin.

The complete cycle of Christ’s suffering, from his arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane to his entombment, is sometimes compressed into a picture type known as 'The Man of Sorrows'. The title derives from the prophecy of Isaiah quoted above. In these pictures, Christ displays the wounds he suffered on the cross and is often surrounded by the Arma Christi (‘the weapons of Christ'). These are the instruments of the Passion, the objects that symbolise Christ’s victory over death. Originally, the Arma Christi consisted of a few objects directly associated with the shedding of Christ’s blood – the lance that pierced his side, the cross itself, the nails and the crown of thorns. But gradually the number of emblems increased.

A Florentine print [P.184-1943] from c. 1500 with a vast, rather bewildering array of Arma Christi visible behind Christ, who holds the wound in his side and is supported in his tomb by a weeping angel.

As well as the cross and nails and the lance that pierced Christ’s side, we see Judas' thirty pieces of silver; the disembodied fist of the soldier who struck Christ; Peter’s sword cutting into the ear of Malchus, one of the men who arrested Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane; the dice used by the soldiers to gamble for Christ’s seamless garment; the basin in which Pontius Pilate washed his hands during the trial; the cockerel that crowed three times as Peter denied Christ. The bird here perches upon the column to which he was tied during the flagellation. Veronica’s veil is visible above the head of the angel.

A variation on 'The Man of Sorrows' is 'The Mass of St Gregory'. Gregory the Great was a sixth-century pope who, while celebrating mass in the Church of Santa Croce ('Holy Cross') in Rome, is said to have had a vision of the crucified Christ surrounded by the instruments of the Passion. Gregory’s vision became a popular subject in medieval art.

This is an illumination from a fourteenth-century Burgundian Book of Hours [MS.3-1954.f.253v], probably made for Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy. His grandson, Philip the Good, who inherited the manuscript, kneels to the right as if witnessing the miracle, while Christ appears on the altar, the blood from the wound in his side dripping into the chalice below. Emblems of the Passion flank him and float above an altarpiece depicting the Crucifixion.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…