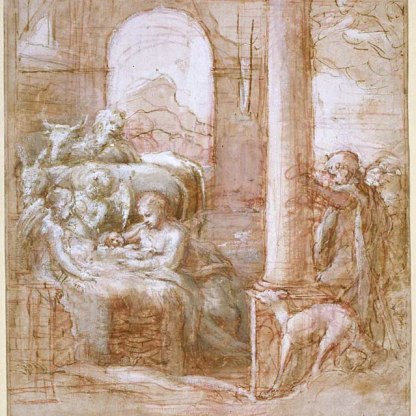

Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist

This small panel was probably used originally for private devotion. Indeed, it has been suggested that paintings such as this, in which the Christ Child is shown fully clothed, were produced for convents of nuns, who might have been offended by divine nudity. Certainly the child's yellow garment catches the eye, with its brocaded cuffs and rectangles of gold embroidery.

But perhaps more noteworthy is the minutely detailed landscape in which the artist locates the holy group. Mary and Christ are no longer seated against the celestial gold background of Byzantine and early Renaissance religious art, like that which we see in Luca di Tommè's c. 1370 altarpiece in the Fitzwilliam 563.

Most of the the physical elements of the landscape – the rich foliage, the distant mountains and rocky outrops – are ones that an Italian viewer could easily recognise. But for all its realistic and familiar detail, this is a highly idealized view. Pinturicchio has made nature literally glow by highlighting it with gold. The edges of the leaves, the branches of the trees, the extremities of the rocks: all catch and reflect a golden light.

Elsewhere gold emphasises important elements within the composition. Originally, Christ's yellow cloak was crossed-hatched with gold to suggest form and volume, but these marks have now faded. The star on Mary's cloak stands out gold against her blue cape. And gold defines the shape of this holy mother's breast, directly in the centre of the painting.

What is, on the surface, an uncomplicatedly peaceful scene, nevertheless contains elements that point to a less than comfortable future for both the children shown. The cross held by John alludes to Christ's Crucifixion, and his own little hair shirt reminds us of the brief, harsh life that this healthy and pious child will commit himself to in the desert.

Having recognised this, perhaps the viewer is justified in looking for further implicit hints at the tragedy of the Passion. Do the buckles on Christ's sandals prefigure the wounds made by the nails on the cross? Do the bare trees behind Mary's left shoulder carry connotations of death to contrast with the trees in leaf to her right? Perhaps they are intended to recall Ecclesiasticus, 14, 18:

'all flesh shall fade away... like a flourishing leaf on a green tree...'

The sixteenth-century biographer and writer on art Giorgio Vasari didn't much care for Pinturicchio. He portrays him as small, deaf, unattractive man, and ends his account of his life with faint praise. 'Besides his other qualities', Vasari writes, '[Pinturicchio] gave no little satisfaction to many princes and lords, because he finished and delivered his works quickly, which is their pleasure, although such works are perchance less excellent than those that are made slowly and deliberately.' Even the diminutive nickname by which he is still known today – Pinturicchio means 'the little painter' – has been taken to suggest that he was a second-rate talent.

But Pinturicchio is perhaps unlucky to have been overshadowed by his fellow townsman, the painter Perugino, with whom he collaborated, and Perugino's outstanding pupil, Raphael. That Pinturicchio's work influenced Raphael, is shown by the latter's Colonna Altarpiece, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which shows the Virgin, Child and infant St John, and is derived from compositions like that on the Fitzwilliam's panel.

Despite Vasari's negative judgement, Pinturicchio was responsible for outstanding work in Siena Cathedral and in the Vatican. Looking at the charming, technically accomplished painting in the Fitzwilliam, we can perhaps agree less with Vasari, than with a twentieth-century biographer of the artist, who described him as a painter 'of quaint and graceful fancy'.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

'Faulkner', who bought it in Italy,

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1880

Dating

Maker(s)

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Paeonia - Greetings card

£3.50

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…