Cabinet with Scenes of the Prodigal Son

Send me 4 or 5 cabinets, 3 with pictures and a perspective and 2 with tortoiseshell on the inside ...

Ralph Hamson of London, 12 April 1652

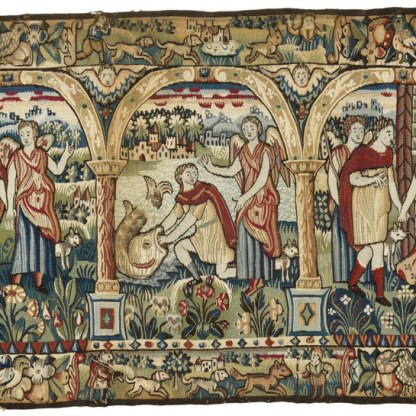

From the outside, with its doors and lid closed, this cabinet is a smart but austere-looking piece of furniture. Open it up, however, and one is presented with thirteen separate narrative scenes, an entire picture cycle illustrating the New Testament parable of the Prodigal Son.

In the centre of this vibrant interior, two small ebony columns flank a central door. Behind this is a perspectiefje – a miniature room with a chequered floor of bone and ebony tiles, walled with mirrors in which are reflected two painted figures. Little chambers like these were popular additions to cabinets in a period fascinated with optical effects.

Pieces of furniture like this were, as Ralph Hamson’s request suggests, highly sought after throughout Europe in the seventeenth century. The best examples might have been used as diplomatic gifts, but most would have adorned the rooms of well-to-do merchants, where they might have functioned as display cases for collections of curiosities. Frans Francken II’s painting A Collector’s Cabinet in the collection of the duke of Northumberland (left) shows just such an item. The doors are open to reveal the painted drawers within, while around we see the owner’s diverse collection: coins, jewellery, prints, seashells, manuscripts and small sculptures.

The centre of production for painted cabinets was Antwerp, the birthplace of Peter Paul Rubens, one of the most brilliant and successful artists of his generation. While Rubens himself never decorated furniture, his colourful and lively style influenced cabinet painters in Antwerp. Left is a small work by Rubens in the Fitzwilliam, The Death of Hippolytus, painted c.1611 in oil on copper [PD.8-1979]. It has been suggested that the seashells visible in the foreground of this dramatic work might have been included to reflect the collecting interests of whoever commissioned it.

Cabinets like this were produced in great numbers until around the 1670s. The large demand, and the fact that the artists were not paid highly for their work, meant that they were produced relatively quickly, given the amount of decoration involved. A painter might have only two weeks to produce a whole narrative cycle, like that here. The carpenter and ebony-worker would have perhaps three or four weeks to finish the bodywork.

The overall decorative impression was, one feels, more important than the individual excellence of each panel, for the quality of painting is not always of the highest. There are inconsistencies that suggest that separate elements were worked by different artists: the larger paintings on the insides of the doors, for instance, are more carefully painted than those on the drawers.

But on the whole the compositions are lively and the landscapes attractive. The scene on the inside of the left-hand door, the first chapter in the Prodigal Son’s fall from grace, is full of charming and telling detail – the playing cards that have fallen to the floor by a rose bush, the small smiling boy who picks the Prodigal's pocket, the village church ignored in the background.

Of the smaller panels, that on the central door to the perspective room is particularly successful. Here the viewer is placed behind the Prodigal’s mother and father, who watch their remorseful offspring approaching from a distance, down an avenue of trees.

Paintings on seventeenth-century cabinets from Antwerp were often copies of famous works, or depicted stories taken from classical myth or the Bible. Moralising scenes of ‘merry companies’ – young men in taverns gambling, drinking and flirting – had been a popular subject in Dutch prints since the sixteenth century, and the Prodigal Son narrative accommodated this taste particularly well.

The choice of the story here – in which the values of forgiveness and repentance are placed above material concerns – was particularly appropriate to a devoutly religious society that was nevertheless enjoying increasing commercial success. The parable stood both as a warning against profligacy and the abuse of wealth, and as a demonstration that such abuses could be repented of and forgiven.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

He perhaps bought it from Messrs Colnaghi, London

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1912

Maker(s)

Note

Formerly attributed to Mainardi, Sebastiano, reattrib. E. Fahy, 1998

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…