Tulipomania

Flowers such as those shown in Jan Breughel’s painting, while still enjoyed today for their beauty, are no longer considered to be particularly rare or exotic. Tulips, hyacinths, anenomes: all are now readily available fully grown or in seed or bulb form. This was not so in the seventeenth century.

A 1629 book by John Parkinson, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris ('Park-in-Sun's Earthly Paradise'), still considered to be one of the greatest works on gardening in the English language, talks at length about the tulip, or ‘turk’s cap'. Parkinson lists 140 different varieties, and notes that,

Our age [is] more delighted in the search, curiosity and rarities of these pleasant delights than any other age I think before ...

The word ''tulip derives from the Turkish tülbend, meaning turban, and was so called by Europeans because of its shape. The first bulbs arrived in Europe in 1554 when Ogier Ghislain de Busbeq, the Austrian ambassador in Constantinople, returned to Vienna.

From Austria, they were bought to the university town of Leiden in the Netherlands in 1593 by the great botanist Carolus Clusius, who did more than anyone to popularise the tulip in its early days in Europe, discussing it extensively in his 1601 book Rariorum plantarum historia ('The History of Rare Plants').

But Clusius had little inclination to exploit the flowers commercially. And it is the thieves who broke into his garden and stole his bulbs that can perhaps be credited with spreading tulip-mania throughout the Netherlands. Soon after the flowers began to be grown commercially, prices for individual bulbs became absurdly high.

In the 1630s a manual worker in Amsterdam earned just under one guilder a day. It has been estimated that an average-sized canvas by Ambrosius Bosschaert, one of the leading Dutch flower painters of the time, cost around 300 guilders. A single tulip in the same period might have fetched as much as 3,000 guilders. Speculation in tulip futures became a favourite pastime. Huge sums were staked upon crops that had yet to be sown. Covert tulip deals were sealed in the taverns of Amsterdam.

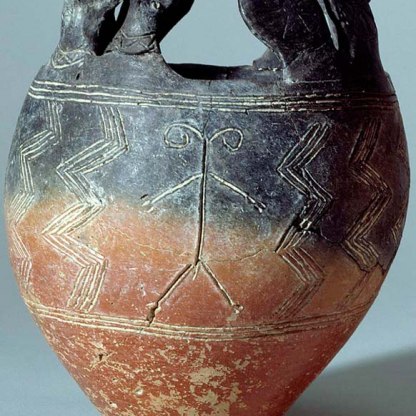

Most highly prized were flamed tulips, in which the petal is streaked with colour, a phenomenon that is actually caused by a virus rather than any virtuosity on the grower's part. Top of the range was the 'Semper Augustus' – a white tulip streaked with red, such as that in the centre of Brueghel’s bouquet.

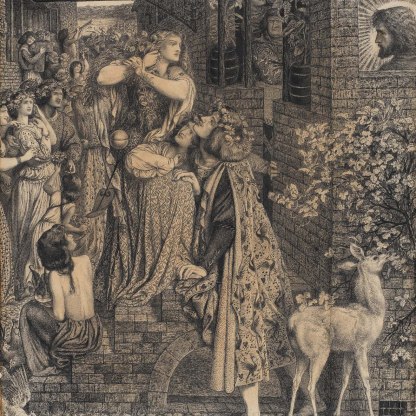

In the midst of this mania, Calvinists scorned the flowers as an extravagance, and railed against the huge sums that they fetched. It was said of one Evrard Forstius, a professor of botany at Leiden University, that he could not see a tulip without violently laying into it with his stick. The tulip was used in popular prints to illustrate the saying ‘a fool and his money are easily parted'. The monkey in Ambrosius Bosschaert II’s 1635 painting in the Fitzwilliam [PD.59-1974] might be an oblique reference to the folly of the tulipomaniacs.

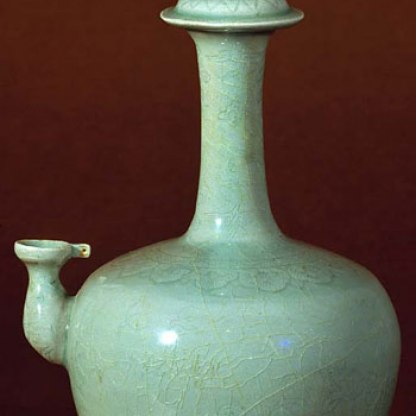

The market collapsed suddenly in 1637. By the end of the year some tulips were changing hands for one per cent of the value that had been placed upon them six months earlier. Yet even after the collapse, flower paintings, and indeed the flowers themselves, continued to be popular, as is attested by the elaborate delftware tulip vase in the Fitzwilliam [C.2607-1928] dating from around 1700.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…