Miniatures

In Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, Act 3, Scene 4, Olivia offers Viola – disguised as a man – a pledge of her love:

Here, wear this jewel for me, 'tis my picture; refuse it not; for it hath no tongue to vex you.

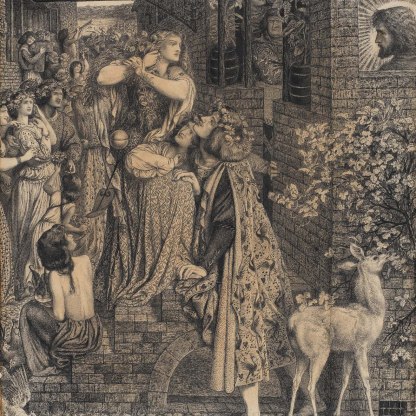

The passage suggests an obvious use for the portrait miniature – as an intimate reminder of a loved one. The picture is set in a jewel and worn close to the heart of the recipient.

In John Donne's Elegie: His Picture, the speaker is leaving his lover to embark upon a long, possibly dangerous expedition:

Here, take my picture; though I bid farewell

Thine, in my heart, where my soul dwells shall dwell,

When weather-beaten I come back, my hand

Perhaps with rude oars torne, or sun beams tann'd,

My face and breast of haircloth, and my head

With care's rash sudden storms being o'erspread,

My body a sack of bones, broken within,

And powder's blue stains scatter'd on my skin;

If rival fools tax thee to have lov'd a man

So foule, and coarse as, oh, I may seem then,

This shall say what I was.

The portrait stands as a memorial to youthful, innocent beauty. One thinks of the two miniatures of Henry Wriothesley in the Fitzwilliam: the one showing an unblemished twenty-year-old [3856]; the second a greyer, wearier, sadder man [3873].

Portrait miniatures were used during the negotiation of marriage contracts between European royal families, and in a similar, but rather less personal way, in international diplomacy. As Nicholas Hilliard writes in The Arte of Limning:

It is for the service of noble persons very meet, in small volumes, in private manner, for them to have the portraits and pictures of themselves, their peers, or any other foreign persons which are of interest to them.

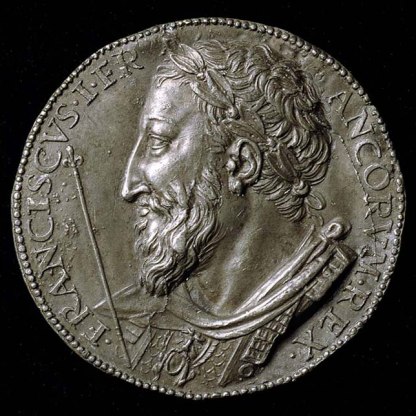

Like their predecessors, portrait medals, miniatures had propaganda value. James I liked to give away miniature paintings of himself as symbols of his favour, and in so doing promoted the new Stuart dynasty.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…