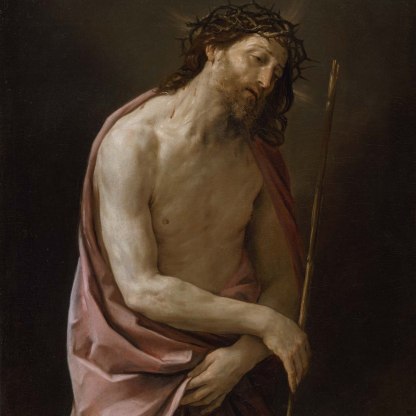

Ecce Homo

In this vivid depiction of human suffering, Guido Reni shows us a Christ entirely alone. He wears the robe and the crown of thorns that, according to Matthew's Gospel, the Roman soldiers forced upon him after his arrest. He has been flogged, mocked and condemned to crucifixion. This is the man who, as he dies, will cry out,

My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?

Reni has drained his palette of any brightness. The background is an unrelenting grey, the 'scarlet' robe a faded puce. Christ's flesh is tinged with green. The title Ecce Homo – 'Behold the Man' – is taken from the words Pontius Pilate used to address the crowd when presenting Jesus to them after he had been scourged. Fresh from the flagellation, this is a body that has had the vitality flogged out of it. Only a few streaks of blood provide any colour on the pale, tired flesh. Reni's Christ here contrasts sharply with his celebrated images of St Sebastian, whose physical beauty often seems to be enhanced by his suffering. An example from the Louvre, Paris, can be seen, left.

Christ's expression and posture here speak of utter weariness: his shoulders slope, his chest sags, his wrists are crossed in submission. He can scarcely grip the reed in his hand – the stick that the soldiers have mockingly given as a sceptre for 'the king of the Jews'. His only physical effort is to hold the robe over his loins, a final, perhaps unconscious, bid for some human dignity. His mouth hangs open and his eyelids droop. The eyes themselves seem to gaze upon the reed sceptre, but they are unfocused.

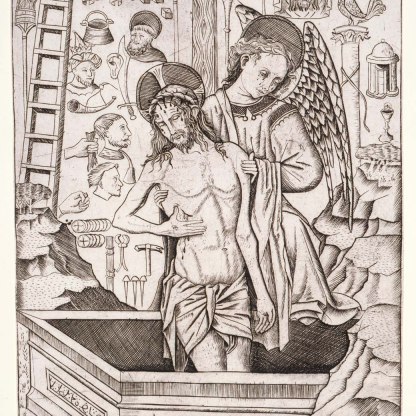

In the imago pietatis – a popular image in which Christ is shown displaying his wounds – a line from the Old Testament Book of Lamentations, 1, 12, is often included:

O all ye that pass by the way, attend, and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow.

The words would make a fitting caption to Reni's painting.

But besides the feelings of pity, even guilt, that the image provokes in the Christian viewer, there is a sense of hope. For there is a hint here at Christ's divinity, a clue to the salvation that this suffering will bring: the faint, cross shaped halo behind his head that shows us that this broken figure is more than human, that he has not been forsaken, and that despite the mocking accoutrements of earthly kingship, he is God made flesh.

Guido Reni was himself an eccentric and rather difficult character. Notoriously pious, he nevertheless ruined himself with a gambling addiction. He was devoted to the Virgin Mary, but was uncomfortable in the company of women and suffered from a paranoid fear of witches. Trying to square his all-too-human quarrelsomeness with his 'divine' talent as a painter, Pope Urban VIII said about him, 'to poets and painters all things are permitted'.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Prince Lucien Bonaparte (1775-1840); exhibited for sale London, New Gallery, 60 Pall Mall, with the rest of the Lucien Bonaparte collection, 1815, when it was bought by Sir Thomas Baring; bought at the death of Sir Thomas Baring, 1848, by his second son, Thomas Baring, who bequeathed it to his nephew Thomas George Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook, 1873; Northbrook sale, Christie's, 12 Dec. 1919 (127), bt. Goetze

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1943

Dating

- Production date: circa AD 1639

Maker(s)

- Reni, Guido Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…